Sustainable Development Goals:

An untapped opportunity for economic communications?

By Duncan Mayall

A mechanism for communicating investment plans

As governments seek out ways to build support and alignment for their investment plans, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals could provide a helpful mechanism for framing delicate trade-offs.

Increasingly, governments worldwide need to explain how their investment plans link to economic growth and broader social development. But doing so is far from easy. Governments must negotiate a fine balancing act to win approval from all sectors of society – each with competing interests and priorities.

Communicating on investment matters for three main reasons. First, and most importantly, governments need to maintain the support of their people. GDP growth is important, but citizens want to know that an investment will lead to tangible benefits.

Second, pressure is growing on governments to demonstrate that investment is socially responsible. Increased scrutiny from outside stakeholders means that “unsustainable” development is likely to attract criticism.

And third, this pressure is also being placed on the investors governments want to attract. Corporations are increasingly aware of the risk to their own reputations related to their international investment and they are under pressure from their investors, employees, and customers on these issues.

However, communication and consensus building are anything but simple in the investment context. For a start, the impact of investments is frequently complex, with trade-offs to weigh up and consider. A new mining development, for example, may create jobs in an impoverished region, but could risk causing environmental damage. A renewable energy facility, which boosts growth and decarbonises energy production, could displace existing communities, with negative social impacts.

The Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) investing framework is the dominant lens through which these issues are navigated at present. ESG is increasingly embedded within the private sector and governments are finding they need to respond with ESG framing of their own.

While ESG has a role to play, it is not a universally applicable concept, and it does have drawbacks. It often leads to a largely risk-based approach to investment, focused on potential problems rather than assessing trade-offs between broader social benefits and downsides. And while many governments may look to develop a sustainable development strategy of their own in its place, this can be less effective when connecting with international audiences.

But, there is an international framework that remains underutilised and to which governments could be giving more consideration: the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

What are the SDGs?

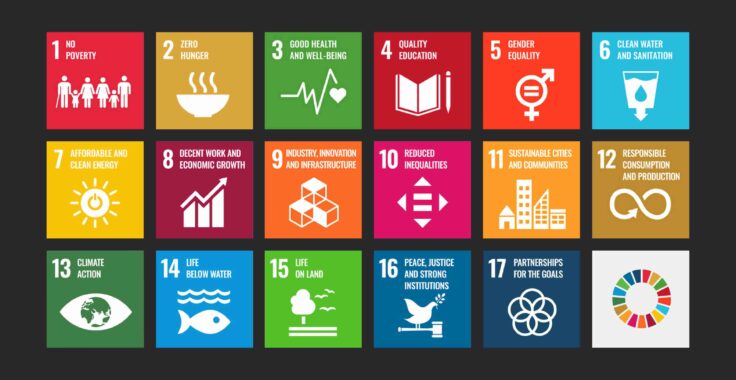

Created in 2015, as part of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to provide “a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.” They reflect an approach which aims to recognise that efforts to relieve poverty, improve health and education, and tackle climate change are all interrelated.

Why the SDGs represent a great opportunity for government communication

1. They are framed around positive contributions rather than risk management.

ESG frameworks have emerged as important tools for portfolio managers, whether they are managing funds dedicated to high ESG standards or simply looking to manage risks associated with environmental, social and governance issues.

ESG investment is beginning to account for a significant proportion of global assets. Last year, PwC’s Asset and Wealth Management Revolution 2022 report found that “asset managers globally are expected to increase their ESG-related assets under management to $33.9 trillion by 2026, from $18.4 trillion in 2021.” 1

However, these frameworks focus heavily on harms and avoiding exposure to the risks associated with these harms. Governments, by contrast, are forced to balance competing priorities in all their complexities. Any investment will involve benefits and drawbacks, and the SDGs can provide a language that allows governments to frame how they have come to decide that the associated benefits of a project outweigh its risks.

This risk-averse framing can be a challenge for emerging markets, especially, where ESG-related risks can be higher. Indeed, recent research from Mobilist found “indicative evidence that ESG mainstreaming can reduce flows to emerging markets and developing economies as growing pressures mount on asset managers to exclude assets with weak ESG scores.” 2 ESG therefore may be incentivising a shift of capital towards “safe” investments in developed countries rather than to the developing countries where it is needed most.

2. They provide a more rounded framework for discussing environmental issues.

With COP28 taking place in November-December 2023 in the United Arab Emirates, pressure around environmental issues is likely to increase for all governments from local and international audiences. While governments must demonstrate delivery against international commitments such as The Paris Agreement, they will also be looking for a more rounded framework within which to position their broader development efforts. This particularly will be the case for any activity that may be seen to run counter to these commitments: for example, the development of local extractive industries or the use of fossil fuels.

For international audiences especially, the SDGs provide a set of development priorities commonly agreed upon at a global level, lending them a degree of international credibility that may not apply to national development strategies. They may also provide governments with a way to negotiate ESG rating systems by demonstrating how the pursuit of the SDGs is supporting outcomes aligned with the goals of ESG and impact investing.

3. They can drive investment towards sustainable development.

As ESG investment becomes more deeply embedded within many elements of the private sector, it is playing a growing role in capital allocation – particularly in developed countries. As governments and the private sector look to address common challenges, SDGs and ESG can complement each other: ESG efforts can benefit from the broader imprimatur of the SDGs, while governments looking to drive investment in the SDGs can benefit from private capital aligned to ESG objectives.

4. They are benefitting from a significant communications effort, raising their salience.

Launched in 2015, with a targeted endpoint of 2030, 2023 has been marked as the halfway point of the SDGs. This has seen them renamed “The Global Goals” in a campaign that appears to be part of an effort to move them from the world of public policy into broader public awareness, not least through an advert directed by Richard Curtis, which uses Al Pacino’s “inches” speech from the film Any Given Sunday to call for action on the goals.

Aimed to reach broader audiences, the campaign also reflects a recognition within the UN that the success of the SDGs will depend on the involvement of the private sector. As a result, future efforts to structure and communicate sustainable development efforts around the SDGs are likely to have more of an impact than they may have had before.

5. They are increasingly linked to financing for developing countries.

One factor driving governments to look more closely at the SDGs is the growing alignment of multinational financiers to these goals, especially when working in developing countries. Governments are finding they need to demonstrate alignment with the SDGs if they want to tap into these important capital pools.

While this can result in an element of “box-ticking,” this alignment is an important opportunity for governments. Previous Consulum engagements in South Africa, for example, included introducing mechanisms to measure the investment pipeline against SDG achievements. This was in direct response to a demand from potential investors for projects that met the SDGs and to understand how the government was aligning with them.

The increasing role of investment promotion agencies

As governments look to drive investment into the SDGs – and to demonstrate alignment with them – one of the main institutions they are turning to are investment promotion agencies (IPAs).

There is now a growing body of research looking at how governments have tried to incentivise sustainable investment through IPAs, and which approaches have been most effective, including helping to “mobilise underexploited sources of finance and expertise, such as multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in the development of hard and soft infrastructure, development finance institutions and special development programmes, as well as investment guarantee schemes to mitigate investment risks.” 3

The urgency for SDG-aligned investment is intensifying as the disparity between current SDG investments and the required amounts expands. UNCTAD recently estimated the growing gap at around $4 trillion, up from $2.5 trillion in 2015.4

Potential drawbacks to the SDG framing

For all their advantages, the SDGs do not represent a solution for all investment and sustainability communications. They have drawbacks, too.

Despite a concerted effort recently to raise awareness and change how they are presented, the SDGs remain largely unknown to a broad public audience, and their ability to connect with civil society may be limited at present.

Likewise, while they can help governments articulate why they have decided to pursue projects that, for example, involve significant carbon emissions, they will not prevent criticism or stop governments from being held accountable for their commitments under The Paris Agreement. Discussing SDGs could even expose governments to additional scrutiny regarding their progress against the goals overall.

And, as ESG factors become increasingly central to investment decisions, governments must recognise their significance alongside the SDGs. Overlooking ESG could lead to missed opportunities in leveraging green finance for economic development, for example.

Conclusion: Rethinking corporate social impact

This discussion points to a wider challenge for governments: categorising the impact that investment – and business, more generally – has on society.

A recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper by Allcott et al seeks to address this challenge by conceptualising corporate social impact as “the welfare loss that a firm’s exit would cause.” 5 Through this approach, they find that “consumer surplus is the primary component of social impact.”

This research serves as a reminder that the benefits of an investment or an economic reform that are easiest to see may not be the most important (the same applies to the harms caused). Initiatives that lead to lower costs and broader consumer choices may not be as tangible as the jobs created in a new factory, but the wider impact may be much higher. It is also a reminder that only looking at ESG risks means ignoring one side of the ledger.

This is where the benefits of the SDGs as a framework become clear. It is hard to find a role for economic reforms that boost competition in a pure ESG framework. But, within the SDGs, there is a clear link to Goal 8 (decent work and economic growth), Goal 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure) and, potentially, Goal 2 (zero hunger).

Likewise, an ESG approach might only see the climate-related risks involved in a new oil refinery, whereas an SDG framework might highlight the counterbalancing positive impact on poverty (Goal 1), affordable energy (Goal 7) and decent work and economic growth (Goal 8).

The SDGs provide a clear bridge between local policies designed to enhance the investment ecosystem and broader global ambitions to improve opportunities for all. This makes them potentially very valuable to governments as they navigate the challenges associated with development, in all its forms.

About the author

Duncan Mayall

Consulum Chief Economist

Duncan leads Consulum’s economic analysis work. He has worked for more than fifteen years in government and corporate advisory. He specialises in economic analysis and its application to policy and communications, focusing on FDI and sovereign wealth funds.

References

[1] “Asset and Wealth Management Revolution 2022: Exponential Expectations for ESG,” PwC, 2022.

[2] “Resetting the ESG Investment Paradigm to Support Emerging Markets and Developing Economies,” Mobilist, 28 April 2023.

[3] “Promoting Investment in the Sustainable Development Goals,” UNCTAD, 15 March 2029.

[4] “World Investment Report 2023,” UNCTAD, 5 July 2023.

[5] Allcott, H., Montanari, G., Ozaltun, B. and Tan, B. “An Economic View of Corporate Social Impact,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 31803, October 2023.