Mastering the economic narrative:

Principles of successful communication for finance ministers

By Kane Silom and James Davies

The impact of economic announcements

“There’s more to come.” A host of issues account for the shortness of Kwasi Kwarteng’s unhappy stint as the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer in 2022. But those four little words were what determined his dramatic downfall.

The pound had already begun plunging as interest rates rose on Friday September 23 – the market’s response to a new budget that featured numerous unfunded tax cuts.1 But when Kwarteng went on BBC One on Sunday to defend the Tory government’s controversial plan, instead of backing down, he doubled down. After dismissing anxiety about excessive borrowing and expressing confidence in the Bank of England’s ability to keep a grip on inflation, he declared: “We’re bringing forward the cut in the basic rate and there’s more to come.”2

On Monday morning, Bloomberg reported, “the selloff in UK assets went into overdrive”, mainly in reaction to that unprompted promise.3 Less than three weeks later, Kwarteng was dismissed, just 38 days after taking office.

Finance ministers are critical to success

Is there any job in government, besides the top job, more complex than that of finance minister? Arguably not. In most countries, the position is the second or third most important after the head of state. The economic and financial policies these men and women help fashion are of the utmost significance to investors, executives, consumers and households. When finance ministers speak, their words must resonate with external audiences that range from unsophisticated, disinterested citizens to sharp-eyed, no-nonsense financiers and CEOs. Internally, they play a central role in setting government funding priorities that shape both the real economy and political reality.

In such an environment, effective governance rests above all on a foundation of choosing and executing the right policies. But how those policies are communicated matters enormously – a reality that too many would-be advisors to finance ministries overlook or undervalue.

Consider Kwarteng’s case. No amount of clever spin could have undone the violently negative reaction to a set of policies that the market simply wasn’t buying. (The woman who selected and then fired him, Prime Minister Liz Truss, was herself forced to resign just six days after her chancellor.) By arrogantly, and at a crucial moment, offering a wide-ranging commitment that no one had asked for, Kwarteng not only failed to buy his battered government much-needed time; he made a bad situation worse.

At Consulum, we believe it is essential that finance ministers master the science and art of being great communicators. That’s why our senior ranks include several former chief comms advisors – including the authors of this article – who have served treasurers and chancellors. Later we will lay out what’s required to get this right. But first, let’s consider two cases where ministers successfully steered the ship of state through tempestuous times.

Success stories from Singapore and Australia

Articulating complicated economic issues in a way that speaks to both sophisticated investors and the general public requires a distinctive skill – the ability to instil confidence without ignoring or blithely dismissing challenges. Tharman Shanmugaratnam, current president of Singapore, was a master of striking that balance in his role as minister for finance (2007–2015).

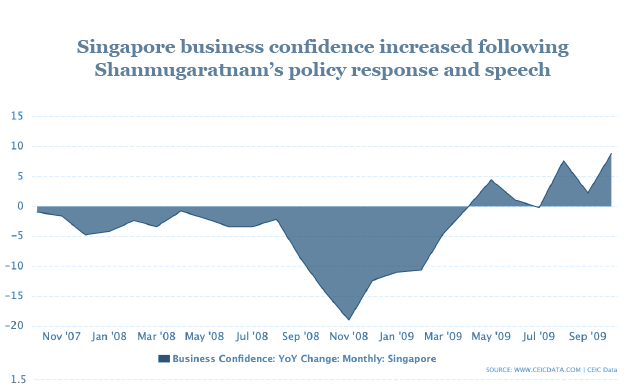

During the 2008 global financial crisis, Shanmugaratnam’s transparent communication and swift, targeted policy responses helped shore up his country’s resilience. When the minister gave a speech at the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Awards in Singapore in November 2008, business confidence was hitting new lows.4 “These are tough economic times,” he acknowledged, pointing to the lack of visibility in the outlook and the likelihood of sharp recessions as the global slowdown deepened.

But Shanmugaratnam also used the occasion to outline a substantial package of measures to “mitigate the impact of the downturn” and help businesses and households “weather a slowdown”, however long it lasted. The ultimate goal, he emphasised, was “to prepare ourselves for opportunities in the recovery”. Over the next weeks, business confidence increased, rising further as Shanmugaratnam and his government backed his well-chosen words with additional expansive policy responses.5

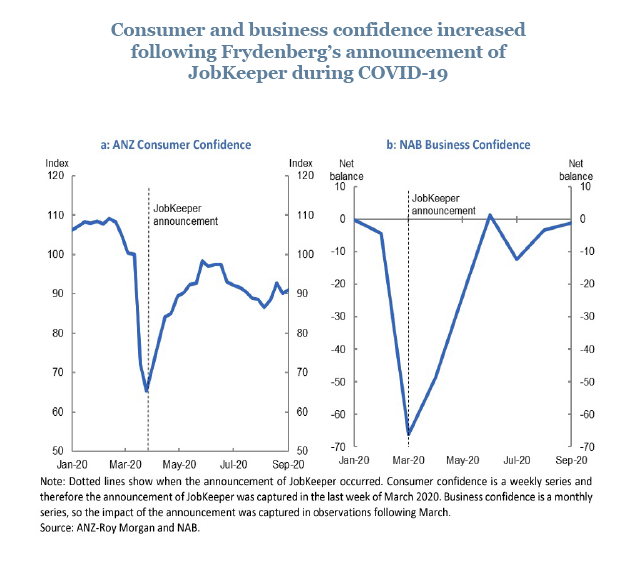

During COVID-19, Australia’s treasurer Josh Frydenberg successfully maintained that same balance of realism and optimism.6 In a speech to the National Press Club on May 5, 2020, Frydenberg clearly stated the enormity of the economic challenge ahead, which he described – backed up by numerous statistics – as dwarfing the 2008 global financial crisis. But he also held out hope, articulating a clear plan “equivalent to the scale of the shock”. A central piece of what he called the government’s “bridge to the other side” was an $88.8 billion programme (final cost) that subsidised continued employment for some five million Australians.7

Frydenberg’s credible, realistic message, backed by the right policy solution – the JobKeeper scheme – reinforced consumer and business confidence at a time when their continued rise was uncertain.

The three essentials of finance minister communications

At the heart of a thriving economy lies the intangible yet potent factor of confidence. When people feel secure, they are more likely to consume, invest and contribute to economic growth. By contrast, a lack of confidence can lead to decreased consumer spending, delayed investments and an overall economic slowdown. The crux of a finance minister’s communications strategy should be to balance confidence and realism in a way that bolsters the psychological resilience of key economic actors despite inevitable uncertainty.

While the right words are critical, those words must be the end product of a rich and considered process. “Winging it” is not an option. To ensure ministers are well briefed and hit precisely the right tone and substance, we recommend adopting what we call the “RPS” model (Resource and Research; Pragmatic and Political; Simple Storytelling).

1. Resource and Research

Step one in any effective government policymaking is to ensure that policy, strategy and communications are integrated and aligned from the start. Nowhere is such integration more important than in finance, where relevant constituencies include not just domestic businesses and voters but also international markets, financial institutions and ratings agencies. The “votes” of the latter – as Kwarteng discovered – typically register well ahead of actual elections.

Getting this right means more than recruiting the best and brightest minds and having them in the room when critical decisions on spending and taxes are made. Importantly, it requires fostering a culture in your operation where ideas and issues are regularly challenged before they go public.

Too often, political leaders surround themselves with “yes-people” who do as they’re told and never criticise. Lack of informed dissent or robust debate leads to poor decision making. The best leaders we’ve worked for and with are open to constructive criticism, actively structuring a process to ensure their views are tested and challenged as they are developed.

During the COVID-19 crisis, for example, Australia’s finance minister could turn to a chief of staff with a strong business and policy background and a director of communications with a strong media and political background. Both were forceful advocates for a simple system of government support that could be easily implemented and understood by the public. But what really mattered was that they were empowered to subject the treasurer and his department to a constant stream of “what ifs” – questions that might be posed by journalists, the opposition, economists, analysts, ratings agencies, or the average Australian. This pressure testing paid off in a popular, well managed job-preservation programme that achieved both political and economic success.

Alongside recruiting experienced people and maintaining a strong culture, finance ministers should make sure they have secured specialised talent to shore up their own weaknesses. For instance, any government worth its salt regularly undertakes research and polling to assist in implementing its agenda. This is a different exercise from the polling aimed at finding out how a leader is doing or how they rate against opponents – standard fare in newspapers around the world. This very specific work can identify policy gaps, anticipate how individual measures may be perceived, and sharpen how such measures are positioned and communicated.

Turning again to Australia, in the weeks ahead of the 2021–22 budget, such polling found that the main priorities for voters were more investment in health services, job creation, and greater support for older Australians. Armed with this evidence, the government ensured its budget communications devoted significant airtime to any measures that demonstrated investment in these areas. By maintaining focus through media releases, speeches, interviews and briefings, it generated front-page news stories like the one below, highlighting precisely these target measures.8

Finally, ministers should keep in mind the need to bring in talent that helps them maintain a robust, well-designed digital presence. Most current finance ministry websites and social accounts could do a lot more to inspire confidence and convey competence.

Communications success: Front page of the Australian Herald Sun the day after the budget was presented, stressing three areas (health, jobs and aged care) identified by government research as important for the government to highlight.

2. Pragmatic and Political

Open and transparent communication is essential in building trust between the government and citizens. In Singapore in 2008, for example, Shanmugaratnam did not downplay the “full-blown economic decline” the world was facing – but he then offered clear, pragmatic details on how his government intended to counter that decline. The tone should be confident, not arrogant. The value of this pragmatism is that it allows one to counter the objections of political opponents while maintaining credibility with markets and business leaders – in essence, to engage in spin without appearing to do so.

In the pandemic’s opening stages, Australia’s Frydenberg knew he had to prepare voters to accept a stunningly large increase in spending, while defeating challenges from both conservatives and progressives. In his speech to the Press Club, he acknowledged that some would say the proposed programme was too costly, “while others say it has not gone far enough and needs to be expanded”. His answer was to position his government as the realists in the room, winning the political argument by appearing to be above politics. “In times of crisis there are no ideological constraints,” he quoted Prime Minister John Howard as telling him in the days before the package was announced.9

3. Simple Storytelling

Shaping economic narratives that inspire confidence and resilience requires clarity, conciseness and a constructive attitude. Ministers should strive to influence public perception and support the goals of their government by projecting success, without downplaying challenging economic conditions.

One essential is always to bring policy implications back to the concerns of ordinary people. Make your ultimate message simple to understand and avoid speaking only to “finance geeks”. After wading into highly technical waters, Shanmugaratnam outlined how his government would meet the global financial crisis by improving lives for property owners, small and large businesses, and workers. And a good tagline or catchy name never hurts. Frydenberg’s government labelled its pandemic subsidy programme “JobKeeper” – simple and easy to communicate. Complicated payment schemes were discussed, but ultimately it was decided to keep it straightforward: $1,500 per fortnight, administered through existing payroll systems.

Another basic principle, as important for finance ministers as it is for financiers and business leaders, is to “under-promise and over-deliver”. Fall short of expectations, which you can often control, and you can be sure that key stakeholders will hold you accountable and score you down.

Consider, for example, the assumptions in your budget. If you forecast a slightly low but credible price for commodities that generate tax revenue and your assumption proves correct, nothing is lost or gained. If the final numbers are betterthan forecast, then this “bonus” revenue can be used to pay down debt or increase spending in priority areas. By contrast, using aggressive or inflated estimations to “pay for” desired future spending risks destroying your credibility as a responsible economic manager should they fail to come to fruition.

Lastly, avoid stepping on your own message. In 2022, Nigeria wanted to boost its budget for the following year to an unprecedented $45 billion. Anticipating market anxiety over excessive debt, the then Finance Minister Zainab Ahmed gave an interview to Bloomberg aimed at reassuring stakeholders about Nigerian economic prospects.10 After discussing rising debt levels and costs, she went on to suggest her government might engage with multilateral financial institutions “to look at the opportunity of how we can restructure our debt to further stretch our debt service period to give us more fiscal relief”.11

The line spooked investors, who saw it as a subtle cry for help and immediately began selling off their Nigerian Eurobond holdings.12 This prompted a swift clarification – that the government had no intention of restructuring the nation’s debt and remained committed to meeting its current obligations – and markets settled back down. But tighter integration of policy, strategy and communications would have avoided the need for such a high-stakes manoeuvre.

When words have the power to shore up or undermine a nation’s well-being, messages must be shaped and delivered with skill, sensitivity and precision. This process will become more critical as the economic underpinnings of our always-on and increasingly interconnected world grow increasingly complex and volatile. Looking ahead, finance ministers and their teams will continue to play a pivotal role in steering nations towards prosperity. Mastering the ability to communicate with confidence and realism will be critical to their success and lasting impact.

About the authors

Kane Silom spent 13 years working in senior positions in the Australian government. As director of communications to the treasurer and deputy leader of the Liberal Party, Josh Frydenberg, he led economic media and communications for four federal budgets, in the nation’s economic response to COVID-19, and through five election campaigns. Kane is a policy communications strategist in Consulum’s Integrated Government Advisory Practice.

James Davies specialises in government strategy and public-policy formulation. He worked in 10 Downing Street under UK prime ministers Gordon Brown and David Cameron and was head of budget policy at HM Treasury, where he led teams to deliver creative solutions to complex and politically sensitive tax and fiscal-policy challenges. James is Consulum’s managing partner.

References

[1] Becky Morton, “Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng hails ‘new era’ as he unveils tax cuts”, BBC News, 23 September 2022

[2] Tom Espiner, “Kwasi Kwarteng: I want to keep cutting taxes”, BBC News, 25 September 2022; Emily Ashton, “Kwarteng Says There’s ‘More to Come’ After UK Tax Giveaway”, Bloomberg, 25 September 2022

[3] David Goodman and Libby Cherry, “UK Market Selloff Slams Gilts, Pound, Piling Pressure on BOE”, September 25, 2022, updated on September 26, 2022

[4] Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Minister for Finance at the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Singapore 2008 Awards Gala, Ministry of Finance Singapore, nas.gov.sg, November 27, 2008

[5] “Singapore Business Confidence Growth”, 2000–2023 monthly % point, CEIC Data, ceicdata.com

[6] One of the authors of this piece, Kane Silom, was serving as communications head in Frydenberg’s administration at the time.

[7] Josh Frydenberg, Address to the National Press Club, Treasury Portfolio, ministers.treasury.gov.au, 5 May 2020; Administration of the JobKeeper Scheme, Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), anao.gov.au, 4 April 2022

[8] “Full Strength Recovery”, 16 page budget special, Herald Sun, 12 May 2021

[9] Address to the National Press Club, 2020

[10] Ahmed’s full title was Minister of Finance, Budget and National Planning.

[11] Ruth Olurounbi, Oliver Crook, and Alice Atkins, “Nigeria Exploring Debt Restructuring, Finance Minister Says”, Blooomberg, October 12, 2022

[12] Anthony Osae-Brown, “Nigeria Bonds Extend Rout on the Word That Can’t Be Unsaid”, Bloomberg, October 23, 2022