From transactional to strategic:

The future of the Chinese-Saudi economic partnership

By Duncan Mayall and Yifan Qin

The modern day partnership between Saudi Arabia and China is a young one. And yet, in just 34 years since its establishment, its importance has increased for both parties.

The most obvious example of this is in trade. In 1995 Saudi-Chinese goods trade was worth around $1.3bn. By last year that figure had swollen to just shy of $100bn, with China now firmly Saudi Arabia’s biggest trade partner.

The nature of that trade has been fairly simple: Saudi Arabia exports the oil that has helped to fuel China’s emergence as a leading global economic power, while China supplies goods that Saudi companies and consumers need. It is a relationship whose structure will be familiar to those who have studied the trading partnerships of either country.

But now, this partnership stands at a crossroads.

Both nations are eager to elevate their relationship to a more strategic level. China has already shown its influence by mediating the Saudi-Iran rapprochement, hinting at a broader role in the region.

Economically, the potential for deeper engagement is vast. Saudi Arabia’s ambitious Vision 2030 and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) present significant overlap, with opportunities for collaboration in technology, investment and trade. Chinese expertise could accelerate Saudi Arabia’s economic transformation, while Saudi investments could reinvigorate China’s slowing growth. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s access to rapidly growing markets in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and beyond positions it as a key partner for China’s international ambitions. The region can also play a larger role as a source of demand for Chinese exports.

However, the partnership faces significant challenges from growing geopolitical fragmentation. Saudi Arabia is clear that its deepening ties with emerging powers like China, India and Brazil will not be at the expense of its longstanding relationships with Western Europe and North America. Rather it is, it suggests, an inevitable response to a world in which non-OECD economies have gone from accounting for less than 20% of global GDP 20 years ago to around 40% today.

Yet, as global divisions intensify, especially between the West and China, maintaining a balanced foreign policy becomes increasingly difficult. The future of the Saudi-China relationship, particularly in areas like advanced technology, will likely be influenced by these global dynamics and the need to protect broader Saudi interests.

Geopolitical tensions may increase the cost of some collaborations, especially in sensitive sectors like high-end and dual-use technologies. However, the untapped potential between these two G20 giants suggests there is still substantial room for the partnership to move to a more strategic and broad-based footing.

At this critical juncture, this paper examines the current state of the Saudi-China economic relationship and its future trajectory. Drawing on recently released trade data for 2023, and detailed information on foreign direct investment (FDI) flows between Saudi Arabia and China (data that was published for the first time at the end of 2023 after a major programme of reforms of FDI data in Saudi Arabia), we place this bilateral relationship within the broader context of China-GCC engagement.

Saudi-China relations and Vision 2030

These developments within Saudi Arabia are not happening in isolation. They are a critical component of the country’s broader economic transformation driven by Vision 2030, an ambitious programme of investment and reforms aimed at reducing Saudi Arabia’s dependency on oil and securing future prosperity.

To succeed in this transformation, Saudi Arabia must harness international expertise and capital. This includes forging new trade relationships to source inputs for emerging industries and finding export markets for non-oil goods and services. This shift represents a departure from Saudi Arabia’s historical economic ties, which have primarily centred on exporting oil and importing manufactured goods.

This imperative is reshaping how Saudi Arabia navigates its international economic relationships, pushing it towards more strategic partnerships. Notably, the growing ties between Saudi Arabia and China are often viewed as a geopolitical counterweight to concerns surrounding the Saudi-US relationship. While this paper acknowledges this perspective, it seeks to highlight the role of the structural economic shifts occurring within Saudi Arabia in driving these shifts.

For example, Saudi Arabia has also prioritised deepening its economic partnership with Japan. Historically, the Saudi-Japan economic relationship focused on Saudi oil exports to Japan, Japanese car exports to Saudi Arabia and a degree of Japanese investment in the petrochemical sector. However, in recent years, significant efforts have been made to broaden this relationship into sectors like financial services, green energy and healthcare, aligning with the goals of Vision 2030.

Similarly, the Saudi-China economic partnership, as mentioned, aspires to evolve from the highly successful transactional relationship of the past three decades into a more strategic alliance. This evolution is likely to involve identifying more areas where Chinese expertise and technology can accelerate the development of non-oil industries—such as electric vehicle manufacturing or solar power—as well as establishing China as a key destination for non-oil exports and Saudi capital.

A critical factor in this relationship is the perception that Chinese investors may be more open to localising production within Saudi Arabia than others. This would make deepening ties with China particularly attractive for Saudi Arabia, as the country’s economic transformation relies on building domestic capacity in new sectors. Localising production, skills and technology plays a vital role in this strategy.

Lastly, while Saudi policymakers appear keen to position Saudi Arabia as a “partner to all”, rather than picking sides amid growing geopolitical fragmentation, they also recognise certain geopolitical realities. Comments from Amit Midha, CEO of Alat, suggesting that the fund would divest from China if requested by the United States, underscore the constraints inherent in efforts by any country to maintain strong ties with both China and the United States. Nonetheless, Saudi Arabia is likely to strive to avoid being forced into making such choices.

Data analysis: Trade and investment

Trade

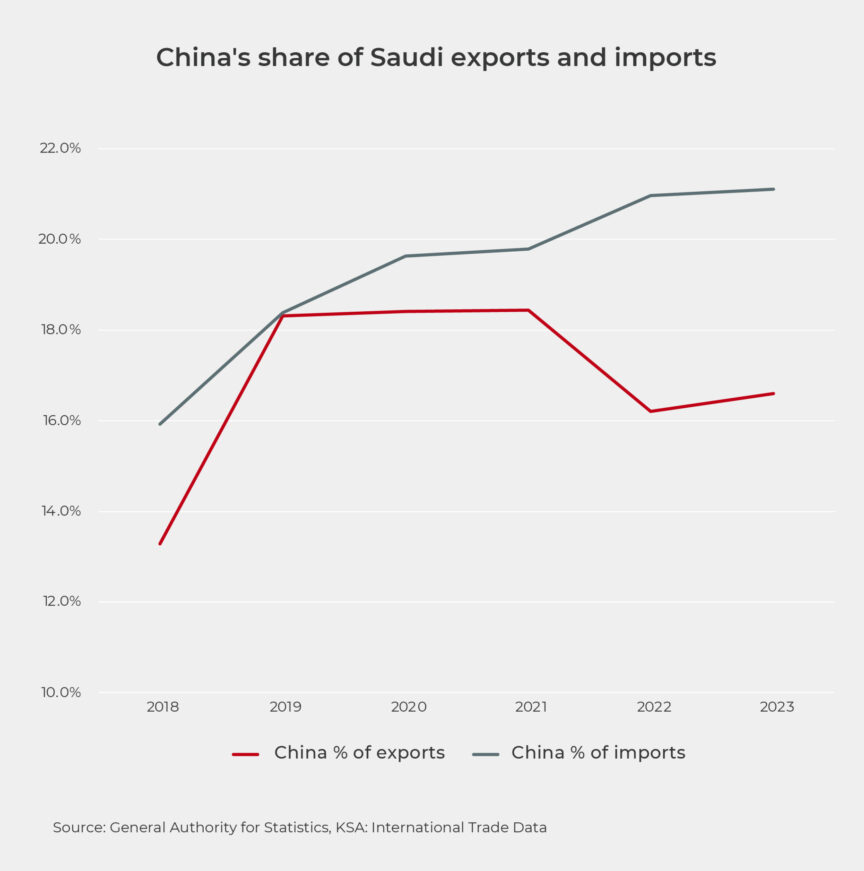

China is Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner, a relationship that has grown in importance in recent years. Saudi imports from China have more than doubled in absolute terms since the start of Vision 2030 in 2016 to 2023, and have increased their share from 14% of Saudi imports to 21%.

Chinese exports to Saudi Arabia are diversified, with machinery, mechanical appliances and electrical equipment making up about 40% of non-oil imports from China. Vehicles account for around 17%, textiles 6% and other manufactured goods 5%. Base metals also play a significant role, comprising around 10% of non-oil imports from China.

The rise in Saudi exports to China, though less dramatic, have seen China’s share of Saudi exports grow from 13% in 2018 to 17% in 2023. These exports are heavily dominated by oil, which accounted for approximately 86% of Saudi’s exports to China in 2023. Within non-oil exports, the petrochemical sector is predominant, with plastics representing around 35% and chemicals nearly half of non-oil goods exports to China.

Investment

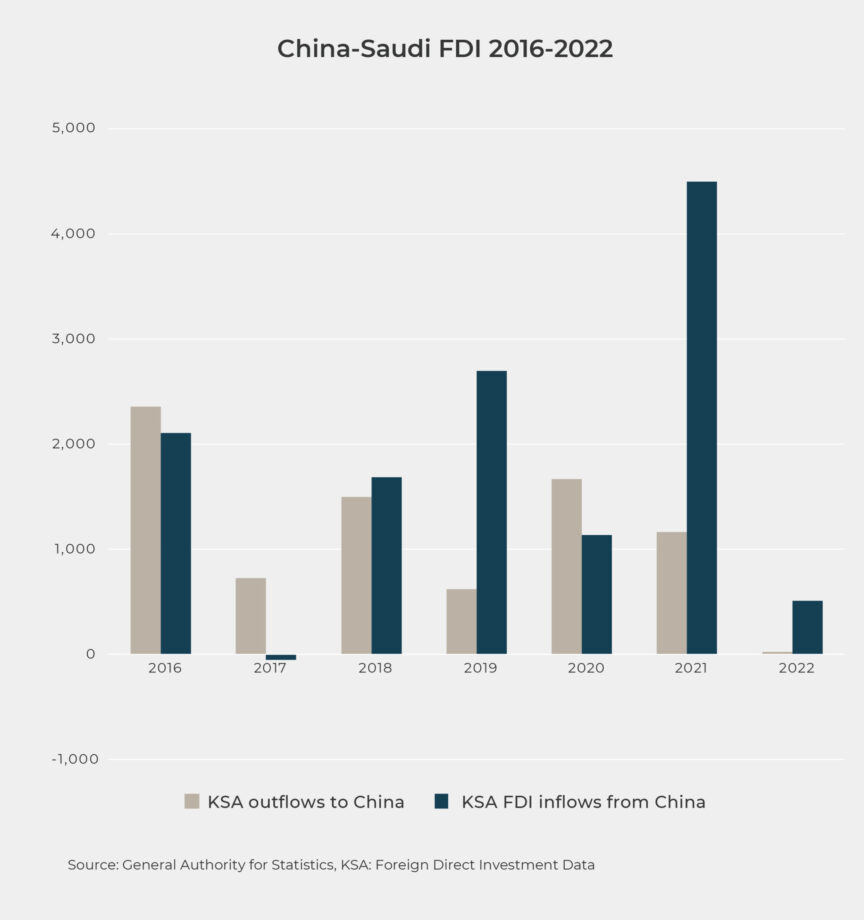

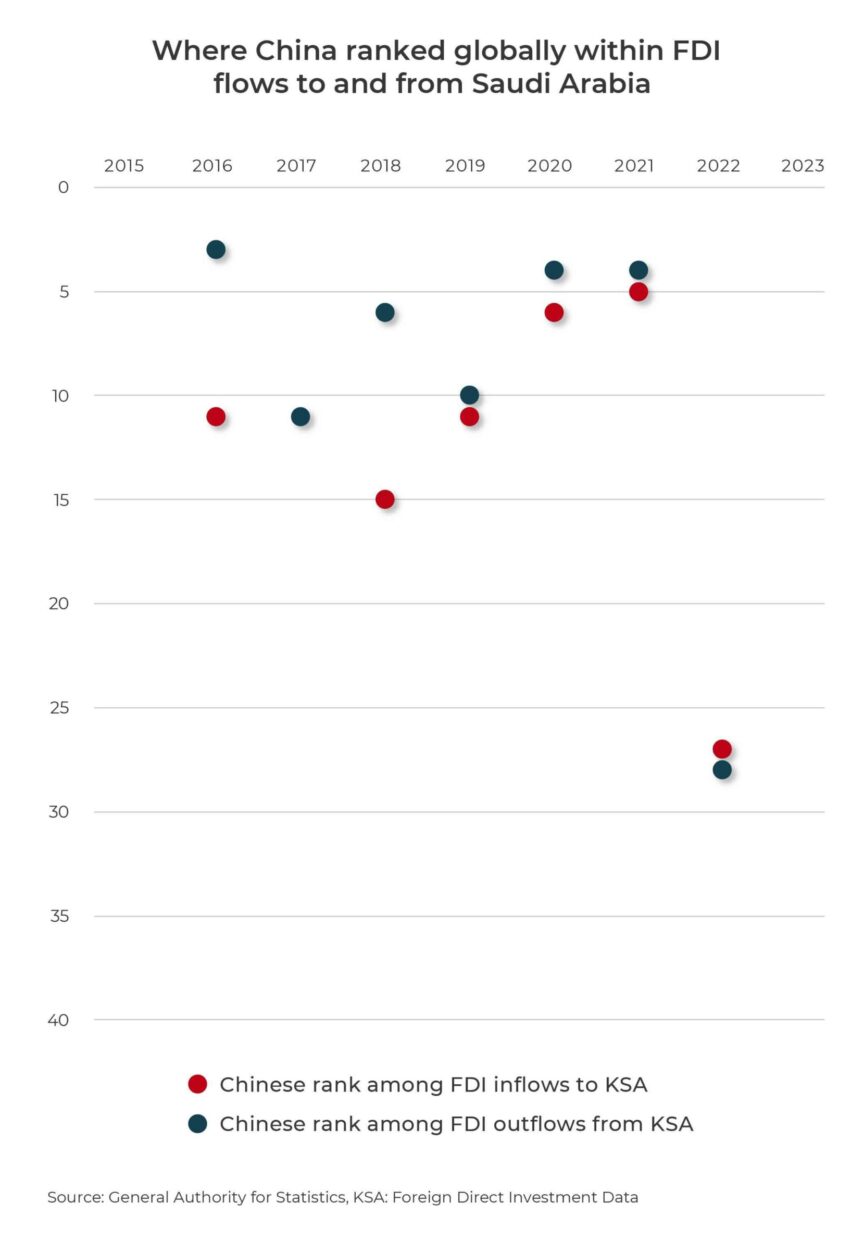

Recent Saudi FDI data, published at a country level for the first time in 2023, reveal that China has emerged as both a significant destination for Saudi FDI and a crucial source of FDI for Saudi Arabia, albeit in a more dispersed field than in the Kingdom’s trading relationships.

While FDI data tend to be volatile on a year-on-year basis, China has consistently been one of Saudi Arabia’s leading investment partners. Among G20 nations, from 2020 to 2022, China ranked as the fourth largest source of FDI inflows to Saudi (around 4% of total inflows) and the fourth largest destination for FDI outflows (around 7% of total outflows).

China has been among the top 15 sources of FDI to Saudi Arabia in five of the seven years since 2016, and among the top ten destinations for FDI outflows in five of those years, ranking in the top five in three of those years.

Petrochemicals have also been a significant focus of Saudi investments in China, exemplified by Saudi Aramco’s $3.4 billion investment last year to acquire a 10% stake in Rongsheng Petrochemical Co. These investments likely aim to maintain market share amid Chinese efforts to boost domestic capacity in the industry and reduce reliance on imports.

As Naser Al-Tamimi, Senior Associate Research Fellow at the Institute for International Political Studies notes, “investments from Middle Eastern countries in China remain relatively modest compared to their available financial assets.” However, there is potential to expand from this low base, with Nicolas Aguzin, Head of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, anticipating that, “the largest sovereign wealth funds in the Middle East may allocate anywhere from $1 trillion to $2 trillion of their investments into China by 2030.”

The path ahead

China has experienced a notable shift in recent years, from being a major importer of foreign investment to a significant exporter of capital – a change driven by the growth of domestic private enterprises that have achieved economies of scale enabling global expansion, and the government’s outward-looking initiatives through the BRI.

In 2023, China’s outward direct investment (ODI) reached $147.9 billion, with non-financial ODI dominating at $130.1 billion. The technology, media and entertainment (TMT), advanced manufacturing, and mobility sectors saw the largest share of overseas mergers and acquisitions (M&A), which grew by 20.3% in 2023. M&A activity in BRI partner countries also increased by 32.4% during the same period.1

However, China faces both domestic and international challenges. Domestically, China must address slowing growth, high youth unemployment, a declining property market and the impact of reduced consumption – all factors that could show ripple effects across the global economy. Internationally, the lingering effects of Covid-19 and ongoing geopolitical tensions continue to strain trade relationships and investment flows.

China’s domestic economic challenges

To tackle these domestic challenges, the Chinese government has introduced a range of fiscal and monetary policies to support its target of 5% GDP growth and create over 12 million new jobs.2 These targets are crucial for securing employment for graduates, and shifting China from low-cost manufacturing to high-value-added production and services, particularly as the country’s largest demographic group approaches retirement – estimated, 28% of the population will be over 60s by 2040.3

The Central Bank has reduced its five-year loan prime rate to help ease mortgage costs for households, mitigating property market slowdown and encouraging short-term spending. Fiscal policy is also set to play a more substantial role, with plans for a 7.8% increase in government spending in 2024 to stimulate economic growth.4

Recognising the importance of FDI, the government released a 24-point plan in March 2024 to boost foreign capital into China. The plan proposes measures to improve the business environment for foreign investors and expand market access in key industries such as biomedicines, artificial intelligence (AI) and the digital economy, as well as advanced manufacturing sectors with significant export potential like electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries and photovoltaic products.

International economic context

Internationally, China remains a key player in global economic growth and cooperation, addressing issues ranging from geopolitics to climate change. This can be seen in China’s shift in focus from the BRI to the Global Development Initiative (GDI) proposed in 2021.

As key industries such as manufacturing gradually open up, China is intensifying efforts to liberalise modern service industries. The 14th Five-Year Plan provides a framework for opening traditionally restricted sectors like telecommunications, energy, health and culture. Schemes like free trade zones will also be piloted more broadly across China, following successful implementations in major port cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen.1

The GDI also follows the 14th Five-Year Plan with investment policy shifting from fixed-asset infrastructure to sustainability-driven and financially profitable investments, in key sectors such as sustainable technologies, innovation, and integrated infrastructure projects.

Saudi Arabia and China have been strengthening their bilateral relationship, particularly as China’s role as a capital exporter continues to grow. China’s increasing ODI aligns with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 goals in diversifying the economy and reducing reliance on oil. China’s investment in high-tech sectors such as advanced manufacturing, technology, media and entertainment offers opportunities for Saudi Arabia to collaborate on projects, creating opportunities to drive domestic innovation and economic diversification.

Moreover, the BRI and the GDI present avenues for Saudi Arabia to enhance infrastructure and connectivity. China’s experience in large-scale infrastructure projects can help Saudi Arabia accelerate the development of critical infrastructure central to Vision 2030 – renewable energy and smart cities.

In navigating domestic challenges, China’s continued investment in key industries, alongside Saudi Arabia’s focus on economic transformation creates a complementary dynamic that can enhance trade, investment and innovation that aids both countries in meeting domestic economic development objectives.

Key opportunities for growth

The potential alignment between GCC member states’ ambitious economic roadmaps and China’s 14th Five-Year Plan offers new trade and investment opportunities. Both China and Saudi Arabia have already benefited from these growing partnerships. As China’s foreign investments shift from large infrastructure projects to focus on green development, industrialisation, the digital economy and connectivity, there is further scope for alignment in areas such as telecommunications, renewable energy, smart cities, AI and technology-oriented businesses.

China has the potential to play a significant role in the growth of Saudi Arabia’s non-oil industries. China’s expertise in new technologies and continued investment in innovation and advanced manufacturing can provide crucial inputs for the Saudi economy. Key sectors such as AI, med-tech, financial services, construction and smart cities are areas of synergy critical for economic development and improving citizens’ quality of life, with the domestic Chinese market having tested and developed technologies to support these sectors.

The Saudi-China relationship not only strengthens economic ties between China and Saudi Arabia but also significantly contributes to global technological advancements and economic stability. For instance, China leads the world in the production of solar panels, electric vehicles, wind turbines and lithium-ion batteries, accounting for 80% of global solar panel production. It is the largest investor in and producer of wind and solar energy, providing cost-effective supply chains, strengthened by domestic demand.

These strengths position China as a pivotal partner in global efforts to diversify energy sources and reduce oil dependence. Through increased trade, strategic partnerships and expertise transfer, China is poised to accelerate Saudi Arabia’s local production capacity, equipment manufacturing, project construction and operations, contributing significantly to the global push for increased renewable energy capacity.

Naser Al-Tamimi observes that Shandong Electric Power Construction’s collaboration with Huawei in Saudi Arabia is centered on large-scale photovoltaic and energy storage projects. The China Silk Road Fund’s acquisition of a 49% stake in ACWA’s new energy unit represents a new phase in China-Saudi Arabia energy cooperation. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s solar module imports from China surged to 2.8 GW, fuelling large-scale projects. Between the second half of 2022 and the first half of 2023, total shipments reached 3.6 GW, supplying 2% of the country’s annual electricity needs.

Saudi Arabia’s investment in, and imports of, Chinese technology underscores its commitment to fostering domestic capabilities. As Saudi aims to enhance its onshoring of capabilities and services, Chinese tech companies have eagerly entered new Gulf markets, with Saudi Arabia serving as a key consumption market and export hub. Huawei has already contributed technology towards Vision 2030, supporting telecommunications infrastructure, with other Chinese firms like Lenovo, SenseTime, Tencent Cloud and Meituan following suit.

Al-Tamimi also notes that Huawei signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Saudi telecom operator Zain in 2019 to introduce the first phase of its 5G network. In addition, Saudi Telecommunications Company and China Telecom Global are collaborating to develop Internet of Things pplications and services in Saudi Arabia, initially focusing on the connected cars segment.

AI, the digital economy, advanced manufacturing and financial services offer significant opportunities for collaboration, emerging as key growth sectors for both nations. Amid the pressures facing China’s tech sector, including US restrictions, reliance on domestic funding and production inputs and challenges within the state sector, Saudi investment into these growth sectors provides crucial support for innovation, even as China navigates domestic economic difficulties.

Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s major project development programme offers substantial business potential for Chinese companies. In 2022, Chinese contractors secured orders worth $4.1 billion in Saudi Arabia, representing 50% of international contracts and 13% of the Kingdom’s market, according to Al-Tamimi.

For Chinese companies expanding abroad, FDI into Saudi Arabia opens new business avenues in the region, allowing them to supply critical industries in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. Simultaneously, Saudi capital inflows into China can help counteract China’s slowing domestic growth and promote innovation in sectors that benefit both nations.

***

For both China and Saudi Arabia, nurturing and expanding their international economic relations is a vital element in achieving their broader strategic ambitions.

Their partnership not only supports Saudi Arabia’s economic diversification goals but also aids China’s efforts to overcome the middle-income trap. Faced with these uncertainties, the China-Saudi collaboration stands out as a stable pathway for fostering economic growth, ensuring energy stability, driving technological innovation and enhancing strategic cooperation.

Unsurprisingly, bilateral investment ties between Saudi Arabia and China have deepened in recent years, complementing China’s role as Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner. The rhetoric on both sides indicates that these developments are seen not merely as an extension of the existing partnership, but as a broadening into new areas and a deepening of the strategic foundation of the relationship.

However, it is evident that these efforts will be influenced by broader geopolitical considerations. While Saudi Arabia seeks to deepen its strategic relationship with China, it is equally clear that policymakers view this as part of a broader strategy to diversify and expand partnerships with leading economies worldwide. This strategy includes Saudi’s close allies in Western Europe and North America, who remain central, as well as new partnerships across South America, Africa and Asia.

As a result, while Saudi policymakers are likely to continue strengthening their partnership with China across key sectors such as high-end manufacturing, ICT and infrastructure, the pace and extent of progress will be shaped by the extent to which these trade-offs align with Saudi Arabia’s strategic best interests.

***

Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those who gave their time and insights during the development of this article, with particular thanks to Robert Mogielnicki, senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, and Naser Al-Tamimi, Senior Associate Research Fellow at the Institute for International Political Studies. All errors in this paper remain ours.

About the authors

Duncan Mayall

Consulum Chief Economist

Duncan leads Consulum’s economic analysis work. He has worked for more than fifteen years in government and corporate advisory. He specialises in economic analysis and its application to policy and communications, focusing on FDI and sovereign wealth funds.

Yifan Qin

Associate Director

Yifan Qin is a government strategy and policy specialist with a focus on international trade and investment. Her experience across trade policies , market access, investment promotion, and international trade dynamics has helped clients navigate complex regulatory landscapes across multiple jurisdictions.

References

- Chow, Loletta. “Overview of China outbound investment of 2023,” EY Greater China, 5 February 2024. https://www.ey.com/en_cn/china-overseas-investment-network/overview-of-china-outbound-investment-of-2023

- “Highlights of Chinese government work report”, XinhuaNet, March 2024. https://english.news.cn/20240305/549ddab14251448e94e56e968bf57777/c.html

- “Ageing and health in China” 1 October 2022 https://www.who.int/china/health-topics/ageing

- Huang, Tianlei “China’s 2024 budget turns expansionary, but will it be fully spent?” Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), 12 March 2024. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/chinas-2024-budget-turns-expansionary-will-it-be-fully-spent#:~:text=With%20all%20four%20budgets%20taken,inferred%20from%20the%20budget%20report.

- “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China”, The People’s Government of Fujian Province, 09 August 2021. https://www.fujian.gov.cn/english/news/202108/t20210809_5665713.htm

Bibliography

- Fulton, Jonathan. Strangers to Strategic Partners: Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations. Atlantic Council, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26037.4

- Sun, Degang. “China and the Middle East Security Governance in the New Era.” Contemporary Arab Affairs, vol. 10, no. 3, 2017, pp. 354–371. University of California Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48599927

- Koruzhde, Mazaher, and Ronald W. Cox. “The Transnational Investment Bloc in U.S. Policy Toward Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf.” Class, Race and Corporate Power, vol. 10, no. 1, 2022. Class, Race and Corporate Power–FIU Digital Commons. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48658236

- Noreng, Øystein. The Evolving U.S.-Russian Energy Rivalry in Europe and the Middle East. Atlantic Council, 2019.

- Hamchi, Mohamed. “The Political Economy of China–Arab Relations: Challenges and Opportunities.” Contemporary Arab Affairs, vol. 10, no. 4, 2017, pp. 577-595. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/48599917.

- Cheng, Joseph Y. S. “China’s Relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council States: Multilevel Diplomacy in a Divided Arab World.” China Review, vol. 16, no. 1, 2016, pp. 35-64. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43709960.

- Al-Tamimi, Naser M. The Rise of China and the Future of Arab Oil: A Changing International Political Economy and Gulf Energy Security. Al Tamimi & Company, 2017.